Washed away: MSU scientist analyzes costs of flood management on the Miss. Sound

Contact: Meg Henderson

STARKVILLE, Miss.—A century ago, the Mississippi Gulf Coast was heralded as the “Seafood Capital of the World” by the U.S. Congress. However, beginning with Hurricane Katrina in 2005, natural and human-made disasters have wreaked havoc on the once thriving seafood industry. A new study by a Mississippi State scientist is quantifying the economic impacts of these disasters on coastal fisheries.

Ben Posadas, an agricultural economist in the university’s Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, is examining the economic impacts of the two 2019 Bonnet Carré Spillway openings on the coast in collaboration with the National Strategic Planning and Analysis Research Center (nSPARC) housed at MSU. Posadas spent the last 30 years quantifying the impacts of fisheries on the coast and the significance of moving from the peak of seafood production to its present state.

“This baseline study is a first step to establish a framework that can collect and analyze data to gauge the extent of the 2019 Bonnet Carré disaster over time and estimate the impacts of future openings,” said Posadas, who also is an Extension and research professor stationed at the MSU Coastal Research and Extension Center in Biloxi.

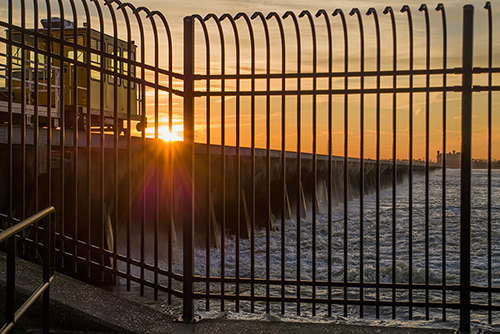

The 7,600-acre spillway—12 miles west of New Orleans, Louisiana—was completed by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1931 in response to the devastating Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Up to 7,000 wooden “needles” resting in 350 bays can open to release excess freshwater from the Mississippi River into Lake Pontchartrain. From there, it passes through a strait called the Rigolets and empties into the Mississippi Sound. The spillway was opened nine times over its first seven decades and six more times since 2008, including twice in 2019.

The two openings of the BCS in 2019—a total of 122 days—left the once-thriving Mississippi Sound nearly silent. The seafood industry ground to a near halt, with oyster mortality over 90% on all but one Mississippi harvest reef and brown shrimp harvests down 82% compared to the prior five-year average. Blue crab commercial landings fared better but were still down 30% compared to the previous five years.

Shrimp and oyster landings—which are more vulnerable to ecological disasters than other commercial species—both peaked in the late ’90s and early 2000s. In 2004, about 4 million pounds of Mississippi oysters were harvested, and in the years after Katrina, restoration efforts revived the market which yielded 2 million pounds harvested and more than $23 million in total sales impacts in 2009.

Between the 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident and freshwater infusions from the BCS roughly every other year, oyster landings steadily declined until the 2019 BCS opening shut down Mississippi’s oyster industry—which remains closed to this day. Shrimp have fared somewhat better, but they, too, have not fully recovered. The annual average harvest was nearly 14 million pounds and $26.2 million in sales between 1984-2004, which has shrunk to less than 8.5 million pounds and $14.9 million since 2005.

In this project, Posadas will use a tool he developed—the Seafood Landings Assessment Model—to analyze Mississippi's annual commercial landings and values from 1950 to the present. However, this investigation will go much further than previous ones, like his major economic impact study of the 2011 BCS openings.

This time, Posadas also will explore the losses to Mississippi’s coastal industries that rely directly on a healthy seafood market: commercial fishing, charter boats, hotels and lodging, and tourism. He will examine and analyze income and employment-related data in these industries to provide a holistic economic scope of the 2019 BCS openings.

Commercial fisheries and aquaculture producers suffer the greatest loss during disasters. Paul Mickle, co-director of the Northern Gulf Institute at MSU and former Mississippi Department of Marine Resources chief scientific officer, said while disaster relief has historically been available to restore marine habitats and industries along the Mississippi Coast, those funds are drying up.

“Federal disaster relief funding is based on a 10-year average of the quantity and value of fish landings,” he said. “When the spillway is opened every other year, the average landings get lower and lower, and we’ve had zero wild oyster landings for the past six years. There’s no way to get disaster relief for our commercial sector under the current system.”

In addition to income and employment data, Posadas and nSPARC will analyze the impact of BCS openings on local and state tax revenue and Mississippi’s “blue economy,” which reaches beyond its coastal counties, impacting the entire state. NSPARC will conduct a survey to assess consumer perception of the state’s seafood-dependent industries and the well-being of workers in these sectors.

“Mississippi’s ‘blue economy’ of ocean-focused industries in Hancock, Harrison and Jackson counties is a major economic engine,” he said. “The Sound’s health is inextricably linked to the health of the coastal economy and culture, the well-being of residents, and the perception of the Gulf Coast as a tourist destination.”

Mississippi State University is taking care of what matters. Learn more at www.msstate.edu.